If you have any buy-to-let properties, watch out for new tax rules due to start in April 2017. In some cases it may be worth transferring personal ownership of property to a limited company but make sure you fully understand the rules as tax is complex. Peter Birkett and Leigh Sayliss from law firm Howard […]

If you have any buy-to-let properties, watch out for new tax rules due to start in April 2017. In some cases it may be worth transferring personal ownership of property to a limited company but make sure you fully understand the rules as tax is complex. Peter Birkett and Leigh Sayliss from law firm Howard Kennedy guide you through what you need to consider

The proposed changes to the tax treatment of income from buy-to-let investments held by individuals rather than by companies has proved controversial.

It is a very specific tax change catching only higher rate tax payers and only buy-to-let landlords – two targets that garner little sympathy from the electorate.

Like the progressive rates of stamp duty land tax that have been imposed on property investors, it is efficient and in line with social attitudes. In this regard it is almost a perfect taxation vehicle for any government. The famous economist Adam Smith would have been proud.

In October 2016, landlords represented by Cherie Booth QC brought to court a case against the tax changes but lost. They are not appealing the decision, although they are still lobbying the government. So it seems that these tax proposals will go ahead. Assuming therefore that this is the future – it pays to be prepared.

Business expenses

The change takes effect as a tax on income without making an allowance for certain genuine business expenses, not just profit. To that extent, it is a radical departure from traditional tax structures on businesses.

Normally, tax applies to income after deduction of expenses and interest on a loan taken out for a business purpose and has historically been deductible from taxable income. From the start of tax year April 2017 that will no longer be the case, with the changes being phased in to reach full effect from 2020.

Buy-to-let income will be taxable, but expenses will be split into two categories (i) mortgage interest and (ii) other expenses. While the latter will remain fully deductible, mortgage interest will only be deductible for basic rate tax.

This has the effect of being tax neutral for those who have an income below the higher tax threshold and hence will protect a section of the buy-to-let community, particularly those who have used property investments as a supplement to a modest retirement income.

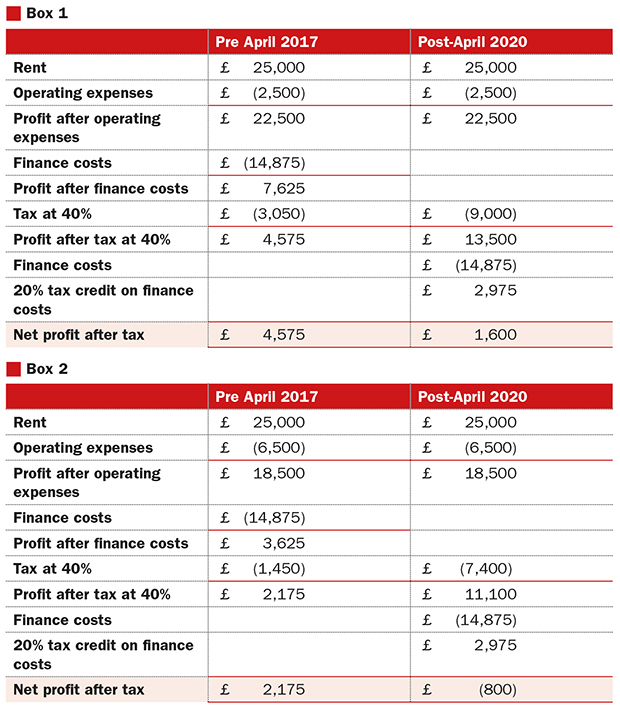

However, for higher rate taxpayers there will potentially be a significant increase in their tax liability. Box 1 gives a calculation showing the increased tax based on rent of £25,000, interest of £14,875 and other deductible expenses of £2,500.

Box 2 shows similar figures but with higher maintenance costs because of work required during the year. It illustrates the risk that a point can be reached where the change in tax means that the expenses of finance, maintenance and tax exceed the income. Rather than the buy-to-let supplementing the owner’s pension, the owner will have to use other income to pay the tax.

Transferring to a limited company

This tax change does not apply to properties held in a corporate vehicle, so landlords owning properties in their own name are beginning to transfer their portfolios into companies to reduce their potential tax bill.

Historically, personal ownership has been the typical pattern for buy-to-let investment. The majority of investors own only a few properties and the mortgage market has been heavily slanted towards personal loans, forcing direct rather than corporate ownership. The market is now changing and loans to corporate vehicles are more common. With more owners looking to incorporate, the supply of mortgage products for them has increased.

Transfer to a limited company is not a complete panacea to tax issues since there can be relatively high tax charges if income or capital is taken out of the company, but, done correctly, in many cases the transfer itself is tax neutral.

There are two concerns on transferring property from personal ownership to a company – capital gains tax (CGT) and stamp duty land tax – but there are mechanisms through which there may be charge to either tax.

Provided the transfer is from a Property Investment Partnership to a company owned by the same owners, and the transfer relates to the whole of the business, and is made in return for shares and nothing else, then the calculations effectively reduce stamp duty to nil and can delay any charge to CGT so that it is only triggered on disposal of the shares.

As with any tax treatment, there is a set of rules which apply and it is vital that these are followed precisely, otherwise the tax treatment may result in either or both stamp duty and CGT.

Stamp duty land tax

The first requirement relates to stamp duty and the properties are held in a Property Investment Partnership. This requires not only joint ownership but also an active business. Simple investment is not sufficient; there must be involvement in the day-to-day operation and management of the properties, such as organising advertising, viewings, lettings, repairs and decoration.

Although there is reference to a partnership, it may be possible to include properties held in joint names provided they have been treated as partnership assets, which will depend on the accounting treatment.

Capital gains tax

Next, it is necessary to consider CGT, and this requires that the transfer relates to the whole of the business. This is not just the properties, but all assets that are shown in the partnership accounts and will include office premises and equipment right down to the paperclips. It is very much an all or nothing test.

Assuming this requirement is satisfied, the transfer must be in return for shares and nothing else. There may be reasons to consider release of equity, for example, to take advantage of annual CGT exemptions, but the temptation should be resisted. No cash payment or transfer of assets of any description by way of exchange is permitted.

Finally, the company must be owned by the same owners as own the assets within the partnership. All owners must agree and all must participate in the company, so this is not an opportunity for owners to withdraw or new investors to be introduced.

Refinancing

It is not a legal issue, but care is required where there has been a refinancing. If the net value being transferred is insufficient to rollover the whole chargeable gain, then a tax charge may be triggered by the transfer to the company. This will require a careful calculation of the original acquisition price for the portfolio, the amount of any chargeable gain and the net value being transferred.

For anyone considering a transfer to a company, the starting point is to go through all of the figures with their accountant to make sure there is no potential for a tax charge lurking in the numbers.

Transaction costs

Assuming all of these obstacles can be overcome, the process is not easy but with adequate planning is not overly complex; however, transaction costs can be high. The transfer will require registration of the change in ownership at the Land Registry and the change in ownership will inevitably require refinancing.

There will therefore be administrative costs, financing charges (which may include early redemption penalties or other breakage costs) and legal fees, with separate representation for the owners and company on one side and for the lender on the other.

Transfer to a company does not alleviate all tax issues. As mentioned above, the extraction of income and capital will generate tax liabilities but there are balancing advantages. The conversion of property into shares allows for sales or gifts of part of the business in a manner which is much easier than transfers of a direct interest in the properties.

The change in structure works best for those accumulating income and capital and who are, therefore, less concerned about the tax consequences of extracting money, but it should be on the radar for anyone with a buy-to-let in their own name.

Each case should be reviewed on its merits, but anyone affected by the change should be considering incorporation, consulting their tax advisers to assess the net effect on their potential tax liability, and speaking to their lawyers and financial advisers to establish whether this is the right approach for them.

Peter Birkett is a senior associate in the real estate team and Leigh Sayliss a partner and head of tax at law firm Howard Kennedy www.howardkennedy.com